Andrew Bartlett has kindly responded with some comments on my most recent article in our conversation series. As I noted then, I sent him an advanced draft copy and I made a couple of amendments prompted by his comments. I left his response as is because I thought it still helped to prompt a few key discussions.

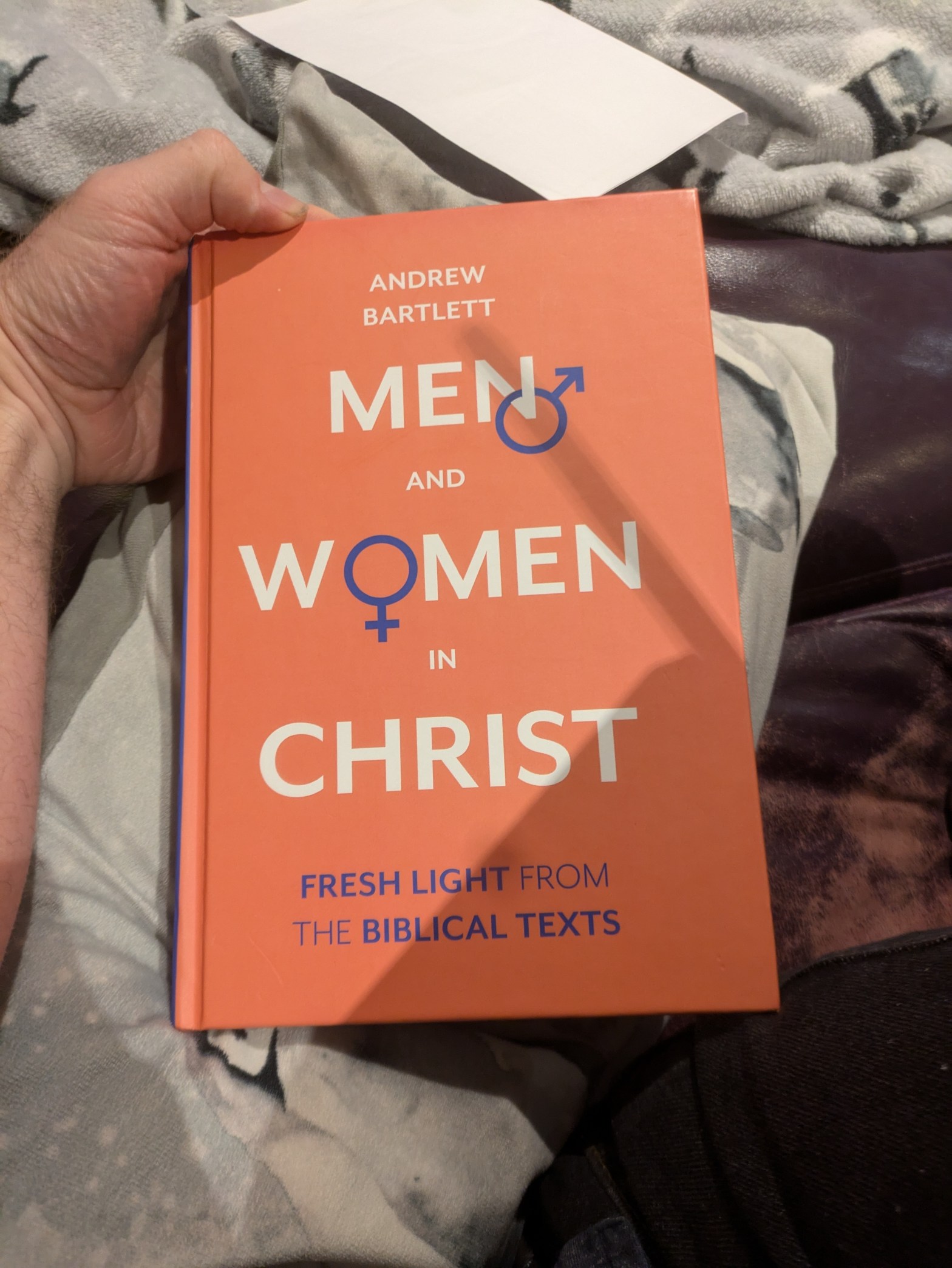

I expect to dig into some of these points in more detail later because I expect them to come up again in our conversation about his book.

First, Andrew says

““Well, Ephesians has already told us how we are to submit to him, in particular where it uses “headship language. Christ is the head of the church (Ephesians 1:22)” But this reasoning does not accurately reflect the text of Scripture. The head and body are united as one (as also in 5:31-32). According to Paul, the church, which is Christ’s body, is seated in the heavenly places with Christ, far above all rule and authority (Ephesians 1:21). In 1:22 Christ is head over all things for the church. The relationship between head and body is described in 4:15-16 – it is a life-giving, nutritious union that facilitates growth in love.”

It was this bit I changed in order to more directly pick up the language of Ephesians 1 and then also draw upon Ephesians 4 as both passages together are needed to support my primary point here which is that Paul tells Christians how to relate to and submit to Christ throughout the letter and that this links to the imagery of head and body.

Ephesians 1 refers to Christ as head over all things and a number of commentators makes the point that Paul uses “headship” imagery concerning Christ prior to and independent of his description of the church as body. Christ is not dependent on the Church for his status. However, whilst Andrew goes with the interpretation “for the church”, if I remember correctly, it is the dative rather than the Greek connective ‘gar’ (for) that is used. So grammatically, “for” is a possible interpretation but the sense here could be “to the church”. In other words we might render the statement something along the lines of “God appointed Christ, head over everything, to the church which is his body.” I think therefore it is legitimate to see Ephesians 1 pointing us to the Christ/Church relationship being seen in head/body imagery even if Christ’s headship functions more broadly.

Secondly, Andrew comments:

“So, what are wives to do when it comes to submitting to their husbands, I want to suggest that it means that they should entrust themselves to their husbands” But ‘submit to’ (hupotassō in the middle voice) does not mean ‘entrust yourself to’. It means ‘place yourself under’ – in other words, treat the other person as more important than yourself. This is why this word works beautifully in 5:21 as a description of Christian humility toward one another.

I will probably discuss the meaning of both kephale and huptosso at some point. I’m not convinced by Andrew’s reasoning here. There seems to be three problems with it. First, he seems to assume only one narrow interpretation of the word. Secondly his reasoning would assume a conflict between the sense o “place yourself under” and “entrust yourself” to. I would argue that to “placed yourself under” involves entrusting to. Thirdly, I don’t think that “place yourself under” is equivalent to “treat the other person as more important than yourself.” I think this is a legitimate aspect of submission and submission certainly involves recognising a person’s authority but that is not necessarily linked to importance, status or value

Next, Andrew picks up on two further points

“Laying down your life, putting the other’s needs first seem to me to be good examples of submission, we have been told to submit to one another (v21) and I don’t think that we can read an exception clause in for husbands.” Yes, we agree on this. And it makes all the more sense when we remember the high pedestal on which husbands were placed in Greco-Roman and Jewish culture. Paul is instructing the husbands to climb down from that high place and be servants of their wives, treating their wives as more important than themselves. This mirrors what Jesus did, coming down from his place in heaven and becoming the slave of all (Philippians 2:3-8, Mark 10:44-45). It is the very antithesis of instructing husbands to exercise their social and legal authority over their wives.

“There isn’t a general Scriptural instruction for men to exercise authority over women” Yes. And it is worth noting that, similarly, there isn’t any Scriptural instruction for husbands to exercise authority over their wives or to lead their wives. This is an important corrective to most complementarian interpretations.

I agree with the first comment and to some extent with his second one. The specific instruction to men is to love their wives However, the point about men and women is that there isn’t a general setting up of gender based hierarchy, the other side of things is not commanded either, women are not commanded to submit to men generally. However, there are specific instructions given on how wives relate to their husbands and the husband is described as “head”.

Andrew is unhappy with my use of BDAG in my citations. He comments

On a point of methodology, I see that you twice cite BDAG as an authority. I have found that BDAG is not a reliable source when considering texts which affect how women are viewed. For example, for phluaros (which Paul uses in 1 Tim 5:13), it gives the meaning ‘gossipy’. This rendering expresses a traditional prejudice about women, but Fee points out that there is no ancient example of this supposed meaning. It refers to talking nonsense (as does the related verb phluareō in 3 John 10). This example is one of many such errors in BDAG.

I’m a little puzzled by this as BDAG is the accepted, standard lexicon for New Testament Studies. This is not to say that it is infallible. However, I don’t think that one NT scholar disagreeing with the lexicon on another completely different word used is a reason not to use and cite BDAG. Fee could be right on that word and despite it being their field of expertise, the lexicon’s editors might have got that wrong. However, it is surely for Andrew to offer evidence as to why they might be wrong on the words in Ephesians 5. I’m not sure that the definitions I cited are particularly controversial though. I mentioned a p.s in Andrew’s correspondence where he notes that the 2017 Tyndale text now includes hupotasso despite the word being missing from the earliest manuscripts available. I agree with him that this departs from the usual conventions in text criticism. It seems an unusual decision and whilst he may be right that it was due to complementarian influence, I don’t particularly see any need from a complementarian perspective to include the missing imperative. It seems more like a stylistic choice to help with flow by making the implied explicit. However, the risk is that it loses the structure, flow and force of what Paul was saying.