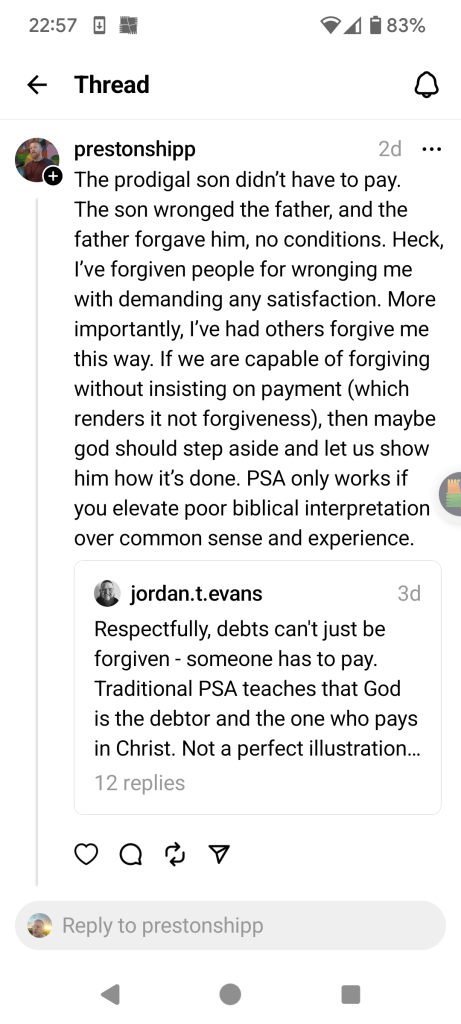

This was other “Threads take” that I referred to the other day.

In the parable of the prodigal son, a father has two sons, the younger demands his share of the inheritance and then leaves home, wasting his share until famine hits and forces him to recognise his folly. He returns home to throw himself on the father’s mercy, willing to come back as a servant. Instead, dad welcomes him back fully as a son with a party.

The argument is that the Father simply forgives without a penalty being paid, there is no sacrifice, no substitution, therefore these things are not required for forgiveness to happen. I have to be honest and say that it is a strangely weak and lazy argument.

First, we might want to point out that it is not the only parable where such themes are not overtly present. The Lost sheep, and lost coin could also be cited along with countless other examples. This should remind us that no parable, or indeed any passage of Scripture is expected to take the weight of all Scriptural doctrine. Rather, we would expect that passage to focus on its primary teaching point and look elsewhere in Scripture for other points. With penal substitution, there are plenty of other examples in Scripture that point to Christ taking our place and bearing our guilt, shame, debt, penalty.

However, it struck me whilst looking at the parable again that whilst it isn’t overt teaching about penal substitution or atonement more generally in Luke 15, there are some important hints and allusions.

- There is a cost, a consequence of the son’s disobedient. The Father (and perhaps the older son to some extent) have to bear this.

- The killing of the fatted calf draws on the OT imagery of animal sacrifices, slaughted and then eaten together as part of the feast.

- The Father is clear that his son was dead but is now alive again. The parable places death and resurrection right at the heart of its message.

Now, in the parable, it is the sinful son himself who leaves home, takes on the status of a servant and is restored to sonship. Does that remind you of anything? The unspoken observative in response to the parable is surely “but it would be impossible for any of us to die and rise.” Jesus takes the place of prodigals. He left his heavenly home, not as a disobedient son but an obedient one. He took on the nature of a servant, he died and rose. Scripture tends to talk both in terms of his eternal sonship and the sense in which he was once again designated Son at the Resurrection. The Father was clear that this was and is and will always be his beloved son.

So, even if it doesn’t matter if this one parable doesn’t point us towards atonement and specifically PSA, it is arguable that in fact it does.

Hot takes often turn out to be cold misunderstandings.