Last week, I engaged with Tim Suffield on whether pastors have jobs or not. Someone who engaged more supportively with Tim was John Barach. He tweeted:

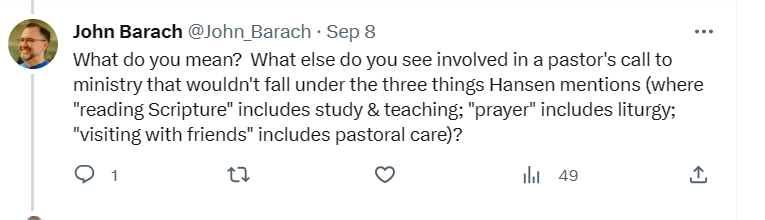

My response was that this is all sounds very pleasant but isn’t how Scripture describes the call to pastoral ministry. He responded by saying:

In our conversation he developed the scenario to include hospital visits and time chatting with older women about their families. By the end of the conversation, the older woman was a widow in his scenario.

I want to pick up more on the specific portrayal of pastoral ministry here and why its problematic but first, I also want to comment on the nature of debate and discussion. There’s something that has crept into debating and argument and has found its way into Christian discourse that I’m not keen on here.

Notice, how it works. First, you set out a proposition, in this case, that pastoral ministry is “leisure”, that we are free to spend our time “reading our Bibles, praying and visiting with friends.” Then when this is challenged you add in further content, your three categories in fact include a whole lot of other things that aren’t obviously apparent in the original proposition. I’m inclined to say that these have been smuggled in. When I pushed him further, John’s response was:

Note here, that he’s quick to tell me what he thinks I understand by the word leisure, he has no basis for doing this and quick to claim I’ve misunderstood his use of the word, when this is a word in common currency with a common understanding of what it means. All throughout the conversation, there’s a sense of words, descriptions and meanings shifting. In a further example, by the end, the older woman is a widow.

Now, here’s the first issue I have with his proposition. Like Tim, he is seeking to argue that a pastor doesn’t have a job, that they are in effect paid for leisure time. As I’ve argued from the start, the Bible does not describe our calling in terms of leisure. It does describe it as work. Timothy is told to do the work of an evangelist, if an evangelist has work to do, so too does a pastor. The calling is described in terms of a soldier set aside for service, a disciplined athlete committed to is training and “a hard-working farmer (2 Timothy 2:3-6). Paul will elsewhere use the example of the unmuzzled ox to show that the diligent elder is worthy of their reward. “The worker deserves his wages.”

To repeat again, pastoral work is work, it’s hard-work, it’s meant to be and that’s a good thing. This is important because some of the insistence that it isn’t a job seems to come from a particular perception of what secular work is like and is about. The frequent refrain seems to be that the pastor is free to set their own timetable, to dwell on a matter, to reflect, to pursue things that interest them even if they don’t seem immediately relevant to the task in hand, to not have to show daily progress and deliver results efficiently.

Yet, whilst there are some jobs where you can measure progress on a daily, hourly or even minute by minute basis, there are plenty where you cannot. In fact, good work design and management often involves taking those micro-management pressures off. An English teacher is working for long term results, among other things, to see the children pass their exams. That’s not the kind ofprodictivity you can measure day to day. They will read to plan lessons, just like a pastor reads to prepare a sermon but if I’ve the freedom as a pastor to pick up something to read and follow up on that isn’t directly relevant to this Sunday’s sermon, doesn’t the teacher benefit from having the freedom to pick up and read a novel that may never make it onto the syllabus?

If we don’t think of pastoral work as work, then that may affect our views of others’ work. It may suggest that our understanding of work and leisure is culturally shaped. We may miss an opportunity to model new creation work.

My second concern is how the wording of the original proposition creates an image of the pastor’s life. It’s leisure, it’s a hobby, I get to do these nice things, a bit of reading, a bit of praying, a bit of time with my friends. Picking up on that word “friends”, there’s much to unpack there. Perhaps the point is that that we should treat church members as friends and there is something to that if it means we think of them as people first, desire to spend time with them and love them. However, remember that in common parlance, we refer to friends as those we have a specific affinity with. We will want to describe them in familial terms as brothers and sisters but we will want to be careful of cliquey language which might suggest that I prioritise my time around those I like and have time for.

Even the language of hospital visits and home visits to elderly members conjures up an image of church life. First, spending time with friends and with older members isn’t something we subcontract to pastors. If the rest of the church don’t see those things as either essential priorities for them or things they have time for then much has gone wrong in our society and our churches. Secondly, it focuses on one type of person and need. When I said that time with older members whilst pleasurable was only a small proportion of my time and of many pastors, John seemed rather incredulous wanting to know what else we were doing with our time apart from studying the Bible, praying and visiting. He of course was missing the point there that it wasn’t “time with people” that was in the minority but rather who needs our time. What about the asylum seeker, homeless person, recovering drug addict, person with severe mental health issues, the wife whose husband has been cruel to her and betrayed her? Come to think about it, what about the restaurant worker, the cleaner on night shifts, the young mum or even the lawyer, doctor and teacher. We seem to be suffering from a rather one-dimensional view of the pastor’s week.

Thirdly, this links in a lot with concerns I’ve been expressing for some time about how we identify and train pastors. I can’t help thinking that this image has dominated a little too much. You end up as I’ve said so often with University churches spotting the guys who find theology interesting in a hobby kind of way, putting them on Ministry Training Schemes and sending them off to Seminary before assistant pastorships in safe, large middle class churches. The message is that ministry is for people who enjoy being in the study. You get to spend your day doing that along with meeting up with friends with similar interests. In return you are expected to do a few home calls to isolated older people who have been allowed to get disconnected from their communities. I fear that this means we miss out on a lot of people who should be in gospel ministry, that pastorates remain vacant in places that don’t meet those expectations and that quite a few young pastors struggle to stay the course when they discover that the role has been mis-sold.

Pastoral work is challenging, hard work, it will involve sweat, toil and pain (at least emotionally). It’s work that you are accountable for, yes ultimately to the Lord but also immediately to your church family. And all of this is good because there is great joy and reward both in the work and in the fruit we get to see.

1 comment

Comments are closed.